here is the NFO file from Indietorrents

———————————————————————

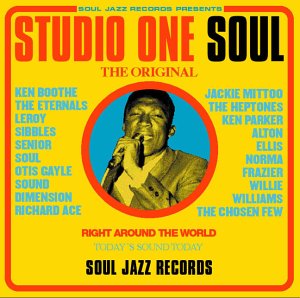

VA – Soul Jazz Records Presents – Studio One Soul

———————————————————————

Artist……………: Various Artists

Album…………….: Soul Jazz Records Presents – Studio One Soul

Genre…………….: Reggae

Source……………: NMR

Year……………..: 2001

Ripper……………: NMR

Codec…………….: LAME 3.92

Version…………..: MPEG 1 Layer III

Quality…………..: CBR 192, (avg. bitrate: 192kbps)

Channels………….: Stereo / 44100 hz

Tags……………..: ID3 v1.1, ID3 v2.3

Information……….:

Ripped by…………: NMR

Posted by…………: viker on 6/1/2012

News Server……….:

News Group(s)……..:

Included………….: NFO

Covers……………: Front

The story of the influence of US music on the development of Reggae has been versioned many times. For all the keen reception in Jamaica of radio stations line WINZ out of Miami and WNOE from New Orleans, and the regular appearance on the Caribbean circuit of such American stars as Aretha Franklin and Curtis Mayfield, it is from the beginning a history driven by the wayward magic of records, the expressive charge and allusive fascination of vinyl, covers, labels. An English chartbuster on the Mod imprint Immediate, for example: ‘The First Cut Is The deepest’, a Cat Stevens song covered by P.P. Arnold with proto-prog-rockers The Nice, cropping up here by Norma Fraser. This is the version excursion of composite musical cultures continuously recycling and renewing themselves, enmeshed with the biggest mass movement for social justice and civil rights of the twentieth century. It is the story of barriers broken down and new solidarities opened up: a kind of ‘musical communion’ as a Baba Brooks title puts it, patterned by the outernational hand-to-hand passage of records, its key setting the sound system dance.

Clement Dodd himself was an avid record-collector, a Jazz connoisseur. His father’s job on the docks turned up records brought by American sailors to exchange for rum, maybe to pay off a pimp. As a migrant farm worker in the early fifties he would return from Florida cane fields with the best new R&B for his Sir Coxsone Downbeat Sound System, still buzzing with the excitement of local juke-joints. Soon he would be licensing records for distribution in Jamaica: and bulk-buying from warehouses in New York and Philadelphia, Chicago and Cleveland, to supply the Musik City Shop he set up in 1959. But exclusives – with scratched-out labels – were a must for Downbeat, and when the American public switched to Rock ‘n’ Roll it was the sudden shortage of killer R&B that spurred Coxsone into the studio. He organised local musicians to produce their own supply of Jump Blues and New Orleans R&B: and Ska evolved from the encounter between these interpretations, such native idioms as Mento, and other favourites like Bossa, Mambo and Merengue, Jazz and Big Band Swing. At first Coxsone would cut these sessions onto dub-plates solely for the use of his sound system, perhaps followed up by a handful of blanks for other deejays. This ideal medium of promotion and market research quickly gauged demand for releases to the public, and so in 1962 – the year of formal independence from Britain – Clement Dodd decided to build the Jamaican Recording and Publishing Studio, better known as Studio One. Behind this affirmation of new nationhood and international ambition is a motive echoed by the Hitsville USA sign on the Motown building in Detroit, and Soulsville USA on the Stax offices in Memphis, and by Motown’s slogan ‘The Sound Of Young America’ where Studio One sleeves would announce ‘The sound Of Young Jamaica’: the power of music to transcend social difference

Unity and peace are the key themes of Curtis Mayfield, justly celebrated as the major Soul presence of the Rocksteady years 1966-68. (He nodded back with a production credit on the Epic album ‘The Real Jamaican Ska’). His songs, arrangements and falsetto lead, his lucid and vulnerable sensibility, poise and sharp tailoring, and the ghost in him of long-time JA favourite Sam Cooke – all these made never-ending impressions. his group themselves stand over a fabulously rich Reggae tradition of vocal trios: here The Eternals stray further than The Techniques from The Impressions’ 1962 hit ‘Minstrel And Queen’ – itself a re-working of ‘Gypsy Woman’ – as lead singer Cornell Campbell’s license elaborates an enraptured reverie about musical inspiration. Curtis’ sixties career epitomises the synthesis by Soul music of Gospel and R&B and also its vital and deepening inter-relation – which Reggae followed – with the freedom movement. Significantly, the Rocksteady years mark a period of artistic decline for Curtis himself, reversed by his last two singles for ABC-Paramount in 1968, during the months Rocksteady gave way to Reggae and soft Soul to more diverse influences. ‘We’re A Winner’ and its version ‘We’re Rollin’ On’ were both still – in Curtis’ words – “locked in with Martin Luther King”. The civil rights leader had been acclaimed on his visit to JA three years earlier: in April he was assassinated. In Chicago, in the spring of 1968, Curtis founded his own independent Curtom Records: swapping classic suits and ties for pastel flares and leather trench-coats, he began to imagine a harder, more militant funk. In Kingston – where the new Black Power politics were more attuned than Civil Rights to the militant nationalism of Marcus Garvey – Bob Marley trimmed his locks and combed out an afro, to the sounds of Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix. With an imitative, inaugural exuberance that harks back ten years to Coxsone’s R&B, Leroy Sibbles versions Charles Wright’s hippy celebration of the sixties’ movement, ‘Express Yourself’.

By the close of 1968, students had torn up Paris streets and American campuses, after the example of Black uprisings in US city after city; Tommy Smith and John Carlos had stood with clenched fists on the podium at the Mexico Olympics; American losses to the Tet offensive had at last swung a US majority against the Vietnam War. In Jamaica Peter Tosh and Prince Buster were arrested during a demonstration against the Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith; and there was serious rioting when the Jamaican government blocked re-admission of the Black Power intellectual Walter Rodney. Several tracks on this compilation directly express political energies which were red hot in this first year of Reggae. Others make their soulful impact by encoding social discontent and political resistance in stories about personal grievance, almost to bursting. Sometimes the Reggae version follows Aretha Franklin’s anthemic interpretation of ‘Respect’, and explodes these allegories : in this way – underlined by his new title, ‘Set Me Free’ – Ken Boothe utterly eclipses Diana Ross’ vocal, and Alton Ellis darkens even further Luther Ingram’s sublime classic. Though this genre of Reggae-Soul versions is conveniently viewed in weak, lightweight opposition to Roots Reggae, classic Soul made available in powerful and sophisticated form the key terms – loss and pain, hope and longing – of the diaspora consciousness usually assigned exclusively in Reggae to Roots. And at the same time themes based on Garveyite ideas of racial purity unravel along those more maverick routes opened up by cultural mobility and change.

Reggae music refreshes and re-invents continuously. Dub, toasting and juggling turn what is familiar into an ambush. These are techniques of resurrection developed for the dancehall which are themselves reworked in remixing and extended formats, rap and turntablism. A Studio One original like The Cables’ ‘What Kind Of World’ courses through many versions before giving Morgan Heritage – its current worldwide hit ‘Down By The River’. Such foundation rhythms have become casually synonymous with Studio One. Likewise nothing in Reggae comes close to the scope and quality of Coxsone’s Soul coverage. This is in part a tribute to his own musical taste, but more importantly to his amazing roster of singers, arrangers like Jackie Mittoo, Larry Marshall and Leroy Sibbles, and to the solidity and longevity, inventiveness and technical brilliance of Studio One musicians. Coxsone was the first in Jamaica to hire a full-time studio band: over the years it is easily a match for such acclaimed American counterparts – all represented on this album – as the Funk Brothers at Motown, the Muscle Shoals Band at Fame, Booker T and the MGs at Stax. Many Reggae covers are routine and empty-handed, churned out quickly for easy cash and cheap thrills. This compilation is more like a series of responses: sophisticated and loving, ebullient and heartfelt, affirmative and searching. The music basks in its sources and influences, in a place all its own.

———————————————————————

Tracklisting

———————————————————————

1. (00:03:33) Leroy Sibbles – Express Yourself

2. (00:02:49) Norma Fraser – Respect

3. (00:02:43) Leroy Sibbles – Groove Me

4. (00:02:50) Sound Dimension – Time Is Tight

5. (00:03:23) The Heptones – Message From A Black Man

6. (00:03:35) Otis Gayle – I’ll Be Around

7. (00:02:49) Jerry Jones – Still Water

8. (00:02:01) Sound Dimension – Soulful Strut

9. (00:03:31) Richard Ace – Can’t Get Enough

10. (00:03:58) The Chosen Few – Don’t Break Your Promise

11. (00:03:23) The Eternals – Queen Of The Minstrels

12. (00:03:15) Norma Fraser – The First Cut Is The Deepest

13. (00:02:19) Ken Parker – How Strong

14. (00:07:05) Ken Boothe – Set Me Free

15. (00:03:13) Senior Soul – Is It Because I’m Black

16. (00:02:49) Jackie Mittoo – Deeper & Deeper

17. (00:03:31) Alton Ellis – I Don’t Want To Be Right

18. (00:03:20) Willie Williams – No One Can Stop Us

Playing Time………: 01:00:06

Total Size………..: 83.74 MB

NFO generated on…..: 6/1/2012 10:03:40 PM